When it comes to discovering new astronomical bodies, sometimes humans are irreplaceable thanks to their skills in pattern detection. But in other cases, computers can spot things that aren’t visible to humans — including a recent instance where an exoplanet was discovered using machine learning.

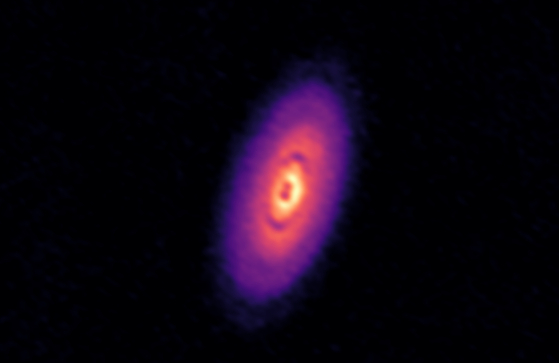

The exoplanet was discovered by University of Georgia researchers within a protoplanetary disk called HD 142666. A protoplanetary disk is a rotating disk of gas that swirls around young stars, and from which planets are formed. Planets are formed within these disks as matter clumps together until it eventually has enough gravity to pull more material in. The researchers looked at a previous set of observations of a whole set of protoplanetary disks, and used a machine learning model to search for exoplanets that might have been missed the first time around. They identified one disk where a planet was likely to be, based on the unusual way that gas moved around within the disk.

“We confirmed the planet using traditional techniques, but our models directed us to run those simulations and showed us exactly where the planet might be,” said lead author Jason Terry in a statement. “When we applied our models to a set of older observations, they identified a disk that wasn’t known to have a planet despite having already been analyzed. Like previous discoveries, we ran simulations of the disk and found that a planet could recreate the observation.”

The researchers say that this is a proof of concept showing that machine learning can be used to make new discoveries of exoplanets, even with data that has previously been analyzed. That could mean more exoplanet discoveries in the future, as well as discoveries being made faster.

“This demonstrates that our models — and machine learning in general — have the ability to quickly and accurately identify important information that people can miss. This has the potential to dramatically speed up analysis and subsequent theoretical insights,” Terry said. “It only took about an hour to analyze that entire catalog and find strong evidence for a new planet in a specific spot, so we think there will be an important place for these types of techniques as our data sets get even larger.”

The research is published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Editors’ Recommendations